Originally published pre-Substack, on January 14, 2020, and included in my collection, From Outside, available in paperback or as a digital download.

Nearly everything about contemporary human life needs to change if we are to seriously address the multiple environmental crises that are facing the planet, but today I will focus on just one topic: trees.

Trees are amazing creatures.

They are found throughout the world, in a wide range of habitats, from elevations below sea level up to alpine; in wetlands and deserts; standing solo or closely communed. The “timber line” is a clear mark on any mountain; above it, needle-bearing perennials give way to lichen-speckled stone that sleeps under snow or basks in the sun, and is softened ephemerally by blossoming annuals.

Mangroves mark coast lines, Junipers rocky ridges, Cottonwoods prairie cricks, Aspens storm-wracked heights and Pines rain-shadow slopes.

From the equator to the tundra, forests thrive thickly, teeming with life micro and macro, nourishing and being nourished by those who gather on their branches, in their shade and among their roots. A pulse of life runs through the whole system, in fluttering wings, flicking tails and stout toadstool stems.

Trees pull water from deepest root tip to highest twig, and transpire it into the sky. They convert sunlight into sugar. They are constantly communicating with each other, with fungus, with insects, and so on and on.

Our ancestors were forest dwellers, eating fruit in the dappled sunlight and calling out to each other in a world abuzz with insects and aflit with birds. We were among many, then.

The planet is lonelier now. Noisier but with fewer sounds; more crowded but with less friends. It’s a mess and getting worse and not many dare to consider what must really be done. But we must speak of these things—if only one by one—and as for trees, we need an immediate moratorium on cutting anymore, anywhere, worldwide, period.

The current custom is that any tree can be cut down for any reason, with exceptions made to save particular ones, here and there, every once in a while. This should be reversed. Instead, it must be forbidden to cut down any tree at all, ever, with exceptions made only for clearly demonstrated need. Need shall be defined most narrowly, not as it currently is, comprised mostly of luxuries.

The following would no longer be legitimate reasons to cut trees: agriculture, ranching, furniture, paper, toilet paper, housing and fuel. Agriculture takes up a far, far bigger footprint than it needs to. We have empty buildings and lots of old chairs and tables. Paper can be made from hemp and toilet paper from bamboo, or replaced with cloth, or we could do as is done in India. Those who need fire to cook and keep warm would be provided for in some other way, as a social subsidy.

Of course all of this is in the context of dramatically rejiggering our society so we are using much much much less of everything, not just wood, but I’ll try to stay on subject.

We must also, obviously, plant as many trees as possible, everywhere we can. In 2018, China assigned 60,000 members of its military and police force to plant trees in order to combat air pollution. It’s hard to think of a better new purpose for the US military, especially given how unpopular it is overseas.

It’s not just that forests are carbon sinks—hence mitigating the contamination humans are pumping into the atmosphere—it’s that when we cut forests, we are being stupid heartless bastards. I choose those words carefully; only someone with no sense or compassion could murder their own elders, and we make ourselves orphans with the saw.

If we cut down all the trees, we’ll be killed by the conditions that result. If we commit such an atrocity, we deserve to die.

I’m not being poetic by calling trees “kin” and Native Americans were not superstitious to speak of “all our relations.” It’s simply a literal truth that everyone on the planet belongs to one big family. That we don’t recognize this in our culture is a blindness born from millennia of untruths, from Abrahamic religion to Greek dualism to Cartesian reductionism. We are hobbled by a cold “humanism” that is a conceit no less deranged than Biblical fundamentalism; both actively deny the vitality of life itself. Both philosophies disbelieve that trees are genuinely alive no less than ourselves. Neither can help us move our consciousness closer to where it needs to be.

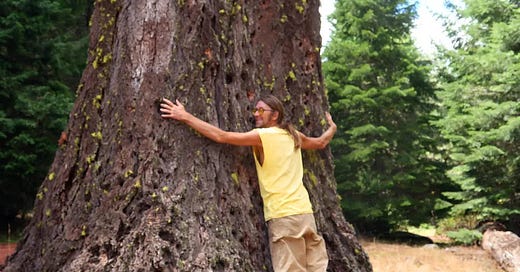

Hugging a tree, on the other hand, is a great start.

With each tree cut we are a little less ourselves, which is to say, a little less human. Some would compare us to pigs or sheep or wolves but that’s a shameful dodge; the implicit message of such slurs—that our mean actions and ugly characters are somehow okay for being “animalistic”—distracts from what we really need to face: our monstrousness.

We are youngsters around trees. The exact age in solar years of any individual tree is irrelevant; I’m referring to the fact of tree-ness as a lifeform, which is ancient compared to our recently emerged model, the bipedal primate.

Our fire-making is significant. Yet far more so is the relationship with fire of some Pines, whose seed cones only open after the resin holding them tightly closed melts in the hot temperatures of a forest fire. That’s an intimacy far beyond our clumsy attempts to wield this element of nature as a tool.

I’ve visited “snag forests,” which are made up of trees killed by fire and bleached white in the sun. Their children fill the landscape around them, bright green with straight spines and the enthusiastic disposition of youth. We humans should not “harvest” the dead trunks; they are now the hunting grounds of woodpeckers and sapsuckers; the homes of wrens, owls and swallows; the perches of raptors. As they fall, they will enrich the soil.

Ultimately, it’s not about us humans leaving everything alone; it’s about healthy interaction, since interaction is inevitable. But right now, we’d do best to be hands off with the forests. We have some old habits to break. Deforestation as policy dates back to ancient history, when trees were cleared for agriculture in the Mideast. Most of the Mediterranean islands and coastlands were clear-cut for ship-building by the Phoenicians and the Greeks. Europe was virtually bare by 1492.

So our culture must relearn respect for trees. We lost it a long time ago. The alternative, though—to continue as we are—is suicide.

To hug a tree, and to feel the life undeniably flowing within, is to embrace living itself. The experience can awaken the senses, including ones you didn’t know you had. It would be a different world if more people hugged trees.

So what are we waiting for?

My elders don't deserve respect. They have sold me downstream. But trees deserve my hugs none the less. You can hug them for whatever reason you want.

Also stop using paper towels. That is so many of their babies.

It seems like there's a large contingent of people who think that a technological solution to the climate and biodiversity crises is the only way to get buy in because it will be easy. That may be true but it won't be effective unless we fundamentally change our relationship with consumption as you explain so wonderfully with regards to trees. A couple wise messages I have received from trees: 1. We will learn to be elders together 2. Never let a good disturbance go to waste.