Attentive readers may notice that I did not post last week, and that this week's is late. Fear not, I'm now making up for that with this 3-part series, to be spread out over today, Sunday and Tuesday. My excuse is that that my time was taken up in prepping for a move, which entailed finishing up a paid gig and passing along important info to the person who would be tending the farm beds after my departure. "Wait, what?" you might be asking. "Wasn't this farm the place you were going to stay all season?" Indeed it was, and more on that later, in part 2.

This installment is a share of garden photos, which I'd been wanting to do all along but hadn't had time for. Part 2 will detail my reasons for leaving, and part 3 encapsulates my big picture reflections on what I learned and how it applies to what I already knew.

At this farm, a market farm, I had four beds of my own to plant up and harvest from personally. Most of my time was spent on general farm tasks and in setting up beds for the market operation, but these beds were of course my favorite and served as a vital home for my heart as well as being a provider for my stomach. They were a mix of veggies, medicinals and one trial grain crop. I only got to enjoy a small amount of everything because most of it wasn't ready yet when I left, but I passed the beds along to a friend of mine at the farm, and she will definitely be appreciating it all.

Every summer I am torn between farm work and wildtending/foraging. I appreciate the wild/feral experiences because they are all about connecting with ecosystems and their denizens and exploring how to interact with them with reciprocity, in part by observing what not to do: that is, how destructive we civilized humans have been to so many places. I appreciate farm work because I love fresh vegetables, and I am deeply interested in how to cultivate respectful relationships with plants being grown for consumption, which is a challenge that is ignored by most people in our culture, including most farmers.

When I'm camping in forest, steppe, desert, or mountain, I don't have fresh greens, and I really miss that. So if I'm going to be on a farm, that's my first priority. This year I grew Arugula and three kinds of Mustard Greens: Green Wave, which has a spicy Wasabi-flavor, from my own saved seed; a cross between Green Wave and Japanese Red that I arranged and saved myself; and something Nikki and I have called, "Elephant Ears," which is a Mustard I got from Chabo, my dear Japanese farmer friend in Portland in the first decade of this century. I don't know what the Mustard's real name is because the packet was all in Japanese with no English on it, lol. I have saved it for years, carefully not allowing it to cross with anything else. (If anyone reading this is friends with Chabo on social media, please share this post with him and maybe he can provide more info!)

I ate these greens fresh nearly daily for a few weeks. Greens are best when they go directly from the garden bed to the cutting board with no steps between, and I relished that pleasure on each and every occasion. The fact that they were grown from saved seed added another level of nourishment beyond the physical, because there's a real relationship there. Chabo used to say that saved seeds do better than store-bought because "they remember you." I'll go with that.

Another priority was Summer Squash because they provide food so reliably once they're off and running. I grew Yellow Crook Necks (from my own saved seed), Green Tint, and Zephyr. The latter two were starts I bought at a local nursery, and Zephyr is a hybrid. I was harvesting a fresh squash almost daily the last month and ate them for lunch or dinner, and sometimes both. I won't buy or eat Summer Squash out of season because it's just no good then, so this is a summer thing only for me.

For later harvest, I planted four kinds of pole beans: Violetto Trionfo (my very favorite bean, a purple Italian heirloom), a green Romano (a flat-podded Italian heirloom), Anellino Giallo (a sickle-shaped yellow snap bean, also an Italian heirloom), and Yard Longs (a different species of bean, from southeast Asia rather than Central America, Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis [literally "one and a half feet"]), which can grow pods up to 20" in length!; plus one bush bean: Red Swan. which is pinkish red. So at some point in the season, I hoped to have handfuls of beans in four colors and four different shapes.

But I got only one purple bean before I left. All the plants had flowers, but were still weeks away from harvest. So sad.

Another summer crop was Black Tail Mountain watermelon. The owner of the farm said they'd never tried growing watermelons in his 40+ years there because he'd heard they wouldn't do well there. Having successfully grown watermelons in Oregon, I thought it was worth a try, since Sonoma County is a few zones warmer. I picked that variety because it was the packet at the nursery store with the shortest maturation date (60-75 days). I put two starts in my beds, and gave the owner 8 for his beds. The plants put on fruits just a couple weeks after transplant and they grew quickly, almost to bowling ball size by my last day. The way to tell if a watermelon is ripe is to look at the curly tendril on the opposite side of the vine from the fruit. Once it has dried to brown completely, the melon is ready to pick. One such tendril, on one of the largest fruits, was already just starting to desiccate, so it looks like watermelons are going to work there! But I won't get to enjoy any.

Planned for fall harvest were Carrots, Root Chicory and Sweet Potatoes. The Carrots were from saved seed where I let like six kinds of carrots of different colors go to flower together: orange, yellow, red, white and purple. The resulting crop a couple years ago was a spectrum of these colors, with a few *pink* carrots! My plan was to set aside the pink ones and save seed just from them, to see if I could get the tone to be dependable. Cuz how fun would that be?!

This was going to be my winter carrot supply, to get me through at least three months. But alas, all I got was a handful of skinny roots, the biggest no thicker than a pencil, which I dug up because I wanted *something.* My friend will enjoy the rest.

I've been wanting to grow Root Chicory for over a decade but had never gotten around to it. This year was finally the year! You roast the root and make a hot beverage out of it, either alone or mixed with other herbs, or with coffee (New Orleans style). The bitterness is good for digestion and there are other medicinal benefits. The greens are also edible, and are what would be called "Dandelion Chicory" because of their shape.

In the very early spring, while house-sitting a cabin in Humboldt County, I sprouted a Sweet Potato from the store and potted it up to grow roots. I then carefully divided it into three parts and planted them in Sonoma County. They just sat there for at least two weeks doing nothing before they started to grow, and it was another month before they started putting out vines of glossy leaves. This is a long-season crop that wants plenty of heat, and I don't know if this location in Sonoma County will be favorable or not, but I thought it was worth a try. My friend will dig them up later and let me know!

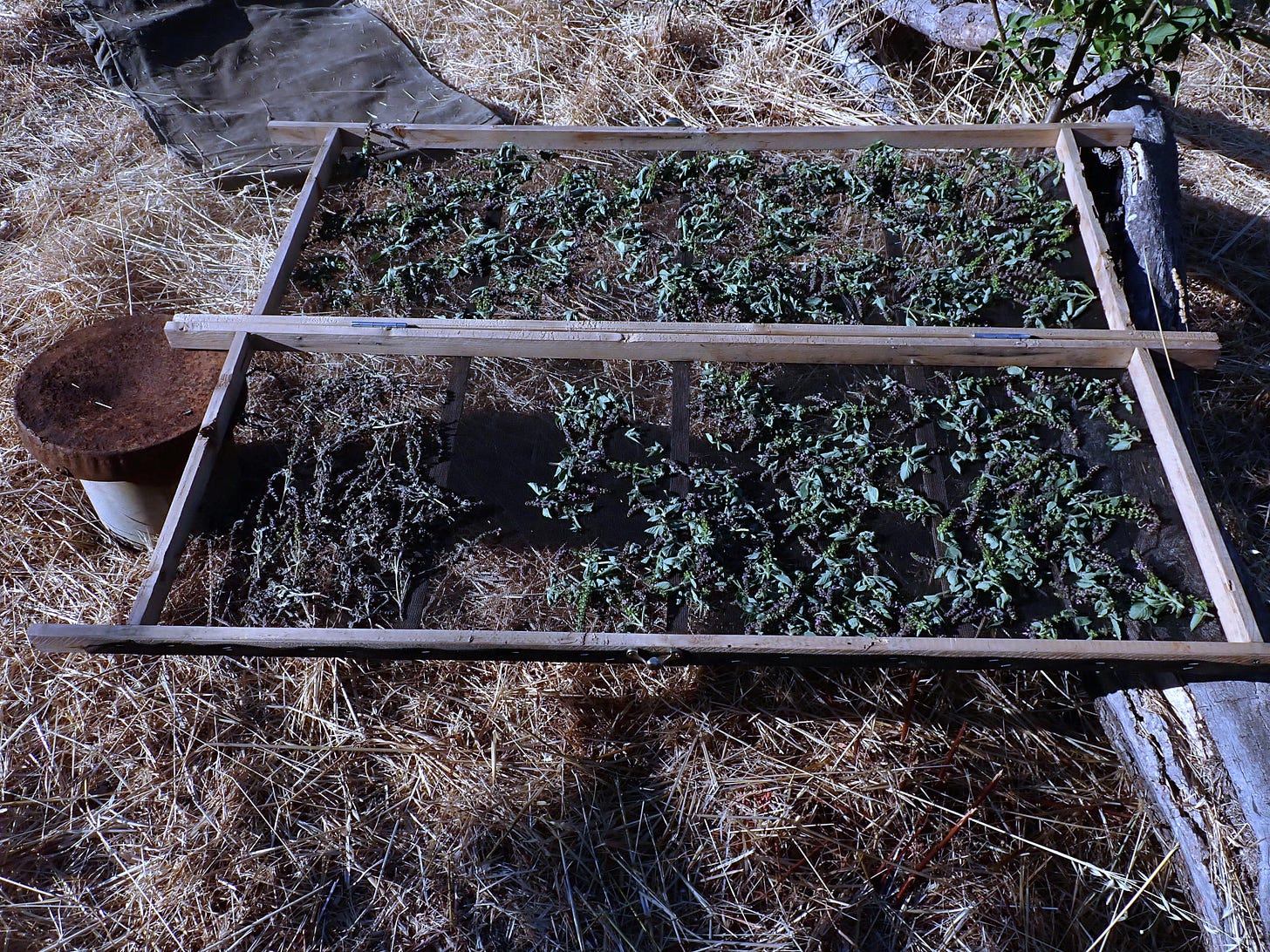

The grain crop was Quinoa, a variety named “Apellewa” from Adaptive Seeds, of Sweet Home, Oregon, a seed-house I *highly* recommend. They grow out their own seeds, or contract out to carefully-vetted local growers and their product is high quality. They also have varieties nobody else does because they have a foundation which supports travel around the world to find interesting varieties and bring the seed back to Oregon to grow out for adaption and increase. When you buy your seeds for next year, start with Adaptive!

The idea of this trial was to see if Quinoa will grow well in Sonoma County. This variety, having been handled by Adaptive in Oregon, should do well at lower elevations. If it thrives, the hope was to plant out a larger plot next year, like some fraction of an acre. As I've pointed out repeatedly, fruits and vegetables make up the minority of calories in the US diet (15-20%) with most sustenance coming from grains, as well as legumes and (for those who eat it) meat. If we're serious about developing a truly sustainable agriculture in the US, we must include grains and legumes! Locally-adapted varieties will be key, and in Sonoma, varieties that can do well with very little summer moisture. Quinoa is famously drought-tolerant once established, so that's why it was picked. My friend also put in a trial patch of Millet, of a variety also offered by Adaptive, because Millet is especially drought-tolerant (being a staple in arid parts of Africa).

I grew Quinoa several to many seasons in Oregon, along with my farming partners there who included Nikki Hill, so I applied that experience to the timing ad spacing we used on this planting. Rather than planting rows, I marked spots eighteen inches from each other (because that's a good minimum final spacing) and planted 5-7 seeds in each spot, thinning down to the most vigorous specimen in each spot. We hand-watered the spots for the first week or ten days, with the seeds sprouting by the third day. After that, watering became less frequent, and at the time of these photos, it had been at least two weeks since they had anything. If these plants look familiar to any gardeners, it's because they are closely related to the common weed Lambsquarters (whose greens are edible and make a passable replacement for spinach in cooked recipes).

In terms of medicinal herbs, I grew Klip Dagga, Spilanthes and Tulsi Basil. Klip Dagga (Leonotis nepetafolia), aka Lion's Tail, is a nervine and beneficial for lung health. The spectacular orange flowers are a hummingbird magnet. Plants typically grow at least 5-6 tall, but can reach heights of 10+ feet under ideal circumstances. One of my absolute favorites, and the inspiration for the name of the seed company that Nikki Hill and I used to run, called Daggawalla.

Spilanthes (Acmella olearacea), aka Tooth Ache Plant, is a perennial from Ecuador, grown as an annual in the north, and is one of the few herbs specifically good for tooth and gum health, hence the name. The foliage and especially the flowers make the mouth tingle and stimulate the salivary glands. They can be eaten fresh or tinctured to make a mouth wash. A very fun plant to grow because the mouth sensations from chewing on the flowers are so intense! These hadn't even budded out yet when it was time for me to go, but I partook of the leaves my last week there. My friend reported that the leaves alleviated the minor toothache she was currently experiencing, which was great to hear.

Tulsi Basil (formerly Occimum sanctum, now Occimum tenuiflorum), aka Holy Basil, is from India and is in the class of medicinal herbs known as "adaptogens" which means they address stress and systemic issues. The aroma of the leaves and the flowers is simply heavenly. There's nothing else like it and they're worth growing just for the joy that the scent imparts. I am a big fan of tea from the leaves and flowers, and I managed to pick and dry three harvests, each bigger than the previous. The last batch finished drying in a paper grocery bag in my truck at my second campsite after departing. I am so happy to have gotten as much as I did, as it's a decent amount for winter. (I gifted the first two harvests to Nikki Hill, because she is also a big fan.)

I also planted three sunflowers from seed I collected in New Mexico, where the plants grow up to 14 feet high and are covered with dozens if not hundreds of small flowers. The seeds are too tiny for human consumption but are very popular with small birds, who feast on them during the cold months if you leave the dead plants in the garden. (Recall that my last name, Sonnenblume, is German for sunflower, so no garden of mine is complete without a representative of the genus Helianthus.) Hopefully they will be allowed to serve that purpose in Sonoma County, and if so, some will invariably volunteer next year.

I was definitely sad to leave a garden at this stage in the season, just as it was all getting going. Not just because I will miss out on the food, but because these plants were my friends; living, breathing creatures with their own volition and consciousness, whose company enlivened me in ways that no human does or indeed can. I am also grateful that I now have the opportunity to spend the rest of the summer in wild and feral places, since that is also so important to me. But the pain of the farewell is real, and this departure only happened for very good reasons, but that's for part 2, “Why I Hate Market Farming.”

Thanks for interesting photos/story. I’m curious as to why the soil at the farm is naked. I feel pained at seeing naked soil as I think soil health is damaged and also there’s that issue of water loss.

i hate market gardening too!