Please share this post on social media! That makes a big difference.

Cars with internal combustion engines (ICE) spew an array of pollutants from their tailpipes including carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and nitrogen monoxide, sulfur dioxide, various volatile organic compounds and particulate matter (not a complete list). All these substances inflict many adverse health effects on humans and other living things, and environmentally they contribute to air and water pollution, acid rain, ozone depletion and climate change (also not a complete list).

As bad as all that is, emissions are only one negative aspect of many. In fact, I’m going to list twenty harms altogether. I’m spelling them out because the push to replace ICE vehicles with electric vehicles (EVs) typically focuses exclusively on emissions, and if we continue to pursue this goal blindly, we and the planet will still be stuck with all the other downsides, a few of which will actually worsen.

Because it’s not just about the car as technology, it’s about the car as culture-shaper. Car-centric values and policy have manufactured physical landscapes designed first and foremost for driving and storing cars. These places are hostile to anyone or anything not inside a car, whether that’s pedestrians, cyclists, animals or other more-than-human life. Such places make up most places in the contemporary urbanized environment, from downtowns to suburbs to exurbs to small towns. It’s a tyrannical infrastructure and the only reason most people don’t think about it that way is because they don't know anything else, which totally isn't their fault. As I’ll lay out here, so much of what’s wrong about cars has nothing to do with their mode of propulsion.

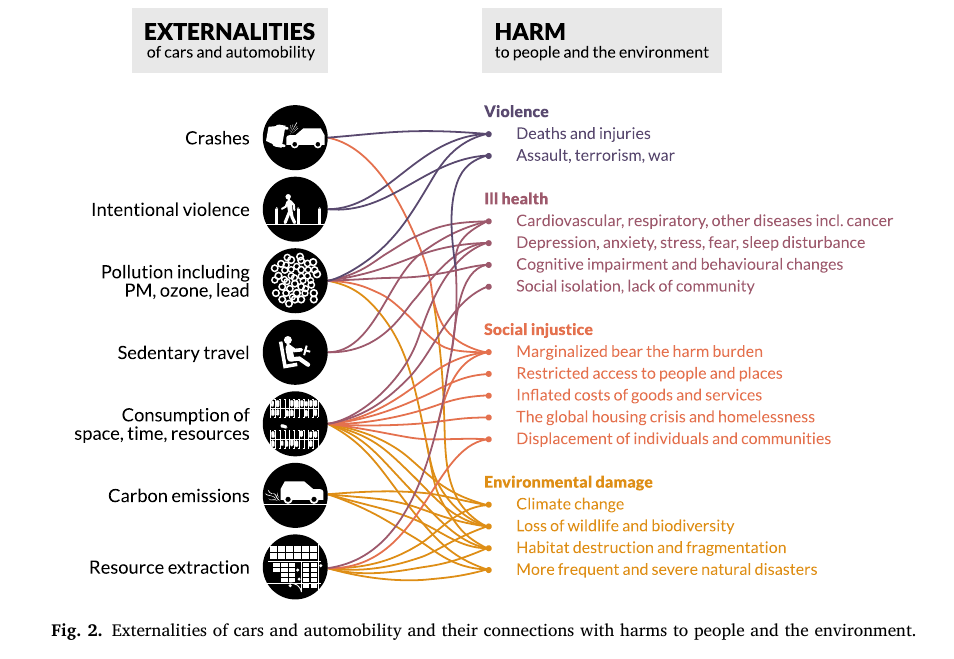

I’ve personally been an urban studies geek since the early ‘90s, so I’ve given all of this a lot of thought, done a bunch of reading, and made many of my own observations of the built environment across the country (and in others) for over three decades. So though I can talk about this off the top of my head, I’m thrilled to be drawing on a recent paper, Car harm: A global review of automobility's harm to people and the environment, by Patrick Miner et al., which was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Transport Geography in February 2024. (Hat tip to CityNerd on YouTube, whose video All the Ways Car Dependency Is Wrecking Us is based on this paper, and is how I found out about it. You could just watch it instead of reading this if you prefer.)

The authors list twenty categories of harm, sorted under four groupings. After each category, I’ve added an abbreviation for how EVs compare to ICE vehicles: S=Same, B=Better, W=Worse. In some cases, EVs will improve one aspect of a category, but worsen another.

VIOLENCE

1. Crashes (W)

2. Intentional violence (S)

ILL HEALTH

3. Air, land, and water pollution (B & W)

4. Noise pollution (B & W)

5. Light and thermal pollution (S)

6. Sedentary travel (S)

7. Dependence and isolation (S)

SOCIAL INJUSTICE

8. Unequal distribution of harm (S)

9. Inaccessibility (S)

Consumption of space, time, and resources:

10. Car-dependent places (S)

11. Streets and expressways (S)

12. Parking (S)

13. Housing (S)

14. Time (S)

15. Financial burden (S)

ENVIRONMENTAL DAMAGE

16. Carbon emissions (B)

17. Pollution and resource extraction (B & W)

18. Tires (W)

19. Other pollution (S)

20. Land use (S)

The tldr is that when we look at the big picture of negative impacts, what we need is fewer cars period, not just different cars.

What follows is my summary of each category. I’ve added my own notes in italics.

VIOLENCE

The authors define “violence” as “bodily physical harm.”

1. Crashes (W)

Car crashes kill 1.3 million people annually, which is 3500 daily, more than 700 of whom are children. Additionally, an estimated 102 million people are injured, too often with permanently life altering effects. While total deaths from car crashes have been going down globally, they have been rising in the US the last few years, which is attributed to the increasing popularity of larger vehicles, which are both taller and heavier.

EVs: Since they are heavier than ICE vehicles of the same size due to the weight of their batteries, more of them on the road could add to the trend of more deaths/injuries

2. Intentional violence (S)

A smaller item, but the authors are nothing if not thorough. In this category they include car bombs, aggressive driving, intoxicated driving, drive-by shootings, and suicide (through intentional inhalation of carbon monoxide). The authors also note that in the US, traffic stops are “a setting for police violence against Black, Latine/x, and Indigenous people.” They also point out that wars have been fought in part for access to oil.

EVs: You can’t use an EV to kill yourself with the vehicles’ own carbon monoxide emissions, but otherwise, it’s a wash for this category. The world has already seen what was arguably the first coup-for-lithium, in Bolivia in 2019 by the US (who else?). I wrote about it at the time here: “Coups-for-Green-Energy added to Wars-For-Oil.” And who can forget this tweet about it from Elon Musk, whose Tesla depends on lithium?

ILL HEALTH

“Cars and automobility negatively affect physical and mental health through a variety of mechanisms including pollution, sedentary travel, and social isolation.”

3. Air, land, and water pollution (B & W)

The authors attribute pollution to two processes: the motor running and material abrasion. The running of internal combustion engines produces gases like nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, and ozone, plus particulate matter. Material abrasion is caused by the friction from tires, brakes and road surfaces and produces particulate matter including microplastics and metallic micoparticles which become airborne, collect in soil and taint waterways. Additionally, oil collects on road surfaces and from there pollutes nearby soil and water and can be inhales in vapor form.

EVs produce much less airborne pollution simply because they lack internal combustion engines, and they don’t leak oil on roads. Their regenerative brake systems produce less brake wear pollution. (B). However, pollution from material abrasion from tires and road friction is as bad or worse because they are heavier (W).

4. Noise pollution (B & W)

“Motor vehicles are the main source of noise pollution in urban areas.” Below 20mph, the majority of that noise with cars is “propulsion noise” (the engine), but above that, it’s “rolling noise,” which is the sound of the tires on the road. With “heavy duty vehicles” the propulsion noise is dominant up to ~47mph. Motorcycles are just always loud. Other noise pollution comes from car horns and car alarms. Noise pollution contributes to “cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, tinnitus (ringing in the ear), hearing loss, anxiety, stress, sleep disturbance, and cognitive impairment.”

EV propulsion noise is so low that federal regulation actually requires EVs to emit sound below 20mph for the safety of pedestrians, especially visually-impaired pedestrians. I can understand why. When I lived in Portland, where I bicycled everywhere, the first time an electric vehicle pulled up behind me at a stop sign I just about jumped out of my seat when I unexpectedly caught it out of the corner of my eye because I hadn’t heard it coming. I realized in that moment how much I depended on my ears to track vehicles around me. Not a complaint, just a funny story. So for propulsion noise they are definitely rated “B” but for rolling noise, they are “S.”

5. Light and thermal pollution (S)

Light pollution, which affects sleep quality, is caused by the artificial illumination of streets and parking lots, which to be fair also benefits pedestrians and cyclists in terms of visibility and safety. Thermal pollution, also known as the “urban heat island effect,” is when the local temperature is increased by paved surfaces including roads and parking lots. Thermal pollution can heighten air pollution, increase incidence of heat stress and heat stroke, and worsen cardiovascular and respiratory disease.

EVs: Same since they depend on the same infrastructure.

6. Sedentary travel (S)

The more we drive and the less we walk or cycle, the worse our health outcomes are, but car dependent environments force us to drive. Lack of exercise increases the risk of “all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality... cancer mortality, and incidence of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer.” Children in particular have become more sedentary, with the percentage walking to school falling from 48% in 1970 to just over 10% in 2017.

EVs: Same since they are also a form of sedentary travel.

7. Dependence and isolation (S)

Car dependent landscapes—like most of the built environment created in the US since WWII—widen the distance between people and essential destinations. Shopping, work, friends, family, healthcare, entertainment, etc., are challenging to reach without a vehicle, and time-consuming to do so with one. “Isolated individuals are at increased risk for the development of cardiovascular disease, infectious illness, cognitive deterioration, and mortality.” Again, the effects on children are more pronounced: “Compared to children who walk or cycle, children who travel in cars have less knowledge about their neighbourhoods, have fewer opportunities for outdoor play and exploration, and gain less experience in assessing risk and becoming independent.”

Finally, there is the isolation of being a human in a car-centric space:

Cars and car spaces dominate urban life. Whether walking, wheeling, cycling, travelling by bus, or simply standing or sitting outside, everyone must negotiate with cars to be allowed their existence. Each time someone prepares to cross a street, they are engaging in a life-and-death decision process. The danger and unpleasantness of traffic reduces rates of walking and cycling and therefore physical activity which is essential to good health.

EVs: Same since EVs will have no effect on built landscapes.

SOCIAL INJUSTICE

For this entire group of categories, EVs have the same impact as ICE vehicles, no improvement.

8. Unequal distribution of harm (S)

“The harm of automobility is unevenly distributed across social characteristics including age, race, ethnicity, sex, gender, wealth, class, and ability.” Examples:

“Crashes are the leading cause of death for people aged 5 to 29 [globally].”

“In Brazil and the US, two large racially and ethnically diverse countries, crashes disproportionately kill Black and Indigenous people.”

“A US study found that people were less likely to stop their cars for Black pedestrians than for white pedestrians.”

Because cars are designed for the “average male,” women are 47% more likely than a man to be seriously injured in a crash and 17% more likely to die.

Crashes are “the main cause of injuries and trauma in pregnant women.”

Men are the majority of people killed in crashes caused by risky driving, an activity that is coded masculine.

“Economically poor are more likely than the economically wealthy to be killed in traffic crashes.”

Wealthy people “cause more air pollution through excess driving, but this pollution is disproportionately inhaled by economically poor people and racially minoritised groups” [recall that air pollution is produced not just by tailpipe emissions but also material abrasion].

I will add that if EVs remain more expensive than ICE vehicles, then harm associated with class will increase, as well as harm associated with race to the degree that race correlates with class.

9. Inaccessibility (S)

The authors are referring to two kinds of inaccessibility: that for people with disabilities, and that which is manufactured by car-dependent environments. For the former, think sidewalks that are uneven, narrow, cluttered or non-existent. Next time you see a curb cut at a crosswalk, imagine whether you would want to use it if you were in a wheel chair. Older ones that are placed on the corner, facing out into the intersection rather than directly at the other corner, are pretty sketchy. Those that lack the grid of tactile bumps can be problematic for people who are visually impaired.

As for the latter, car-dependent places without adequate public transportation are disabling for people who don’t have their own vehicles, leading to what the authors call physical inaccessibility and social inaccessibility, which overlap. They call this what it is: “social oppression.” They quote another paper:

Automobility promises the annihilation of distance, but prioritises some people’s journeys at the expense of others’. Some distances become larger, as when dual carriageways [four-lane divided highways or stroads] and fast one-way systems bisect inner-city areas, speeding up commuters while forcing local people to detour. Rather than dissolving space, the car economy redistributes it, and most disabled people are among the losers, along with people in poor neighbourhoods and children.

Consumption of space, time, and resources:

10. Car-dependent places (S)

Automobility makes possible the spread-out suburban and strip-mall environment we are currently saddled with, where zoning regulations keep housing separate from retail and from work, enforcing the need to drive everywhere to do anything in a self-reinforcing loop. In the US, racist policies including redlining were central to the initial creation of these environments, and though officially struck down, still shape our present situation.

11. Streets and expressways (S)

The authors note that although streets are technically public, they end up being dominated by cars, just in terms of how much physical space they take up: “While moving, cars consume an estimated 1.39 m2 per hour per person compared to 0.52 m2 for bicycles, 0.27 m2 for walking, and 0.07 m2 for buses.”

Expressways, e.g., freeways or interstates, are incredibly space and resource intensive. Between 1957 and 2010, interstate construction in the US “cost at least US$1.4 trillion and required the movement of 38 billion metric tons of earth—equivalent to 116 Panama Canal construction projects… [and] displaced an estimated 1 million people from their neighbourhoods.” Interstates continue to fragment urban areas all over the US, with a host of adverse effects on quality of life. There’s really not a city of any size that isn’t still marred by them.

12. Parking (S)

We take parking for granted and don’t usually think about it much but it takes up a tremendous amount of space in the built environment. “On-street parallel parking consumes approximately 10-19 m2 per car and off-street parking consumes about 25-33 m2 per car.” That ends up being a lot of space. There are downtowns where parking takes up more land than buildings. In the suburbs, parking is “free” but not really. The cost of its construction and upkeep it is rolled into the prices charged in the stores, so anyone arriving on foot, by bicycle, or public transportation is subsidizing drivers with their purchases, like an invisible tax. Virtually every municipality has parking minimums in their zoning codes, so businesses are required to provide a certain amount whether or not they want to. Such minimums are intended to cover the busiest day that could happen, meaning that most of them are never actually filled to capacity, and the real estate wasted on pavement is denied other uses like green space, more buildings, bicycle infrastructure, etc.

13. Housing (S)

Scarcity of space for housing—and the resulting high cost of housing—is exacerbated by the amount of space in urbanized areas dedicated to cars and their storage. The authors note that the 25-33 m2 taken up by one off-street parking space is “about the same size as the average living space per person in China, South Korea, or Spain and larger than the average living space per person in India, Brazil, Mexico, or Poland… meaning that at least 40% of the global population lives in countries where the average living space per person is equal to or smaller than one parking space.”

The cost of building and maintaining parking also increases the costs of housing, both in detached homes and apartment buildings. A cyclist living in an apartment is paying higher rent to pay for infrastructure they don’t need, and so is subsidizing their neighbors with cars. The authors wryly comment that “bundling parking with housing creates “free” homes for cars and more expensive homes for people.”

14. Time (S)

Commuting through vast car-dependent environments, being stuck in traffic and searching for parking take up big chunks of time. Because driving requires one’s full attention, this time can’t be spent doing something else, like reading or doing the crossword as is possible on a bus or a train.

15. Financial burden (S)

Car ownership, which is a de facto requirement in car-dependent places, costs money. Besides gas and insurance, there are repairs. Society at large pays too though. The authors point out that the total cost of automobility is not shouldered by the vehicle owner alone because so many costs are externalized, like the aforementioned “free” parking.

“A German study estimated the total lifetime cost of one car to be €600,000 to 957,000 of which €250,000 to 280,000 is paid for by government subsidies and higher prices for goods and services. In the European Union, a study suggested that cars cost society €0.11 per kilometre while walking and cycling provide a positive benefit (mainly via health effects) of €0.37 and €0.18 per kilometre.”

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration cites these figures for the US:

Those not directly involved in crashes pay for roughly three-quarters of all crash costs, primarily through insurance premiums, taxes, congestion-related costs such as lost time, excess fuel consumption, and increased environmental impacts.

Traffic crashes cost taxpayers $30 billion in 2019, roughly 9% of all motor vehicle crash costs. This is the equivalent of $230 in added taxes for every household in the United States.

These losses include medical costs, lost productivity, legal and court costs, emergency service costs, insurance administration costs, congestion costs, property damage, and workplace losses. These figures include both police‐reported and unreported crashes.

When quality-of-life valuations are considered, the total value of societal harm from motor vehicle crashes in 2019 was nearly $1.4 trillion.

The publication Stacker lists other costs of cars and car-culture that are subsidized, among them:

Loosely enforced and arbitrarily set speed limits

Lack of vehicle safety laws to protect pedestrians and cyclists

A mortgage interest deduction drives suburban sprawl

Tax laws favor car ownership

Pedestrians have limited ability to sue drivers and can’t sue car makers for defects

Hit and runs are rarely prosecuted

Out-of-pocket car expenses don't cover the cost of roads

Unmentioned by the authors is the Ponzi scheme style of financialization that supports the suburbs for now, but cannot be sustained. For the details of this, see Strong Towns’ “The Growth Ponzi Scheme: A Crash Course.” Basically, low density car-dependent infrastructure doesn’t produce enough tax revenue to pay for its own upkeep. So far, this subsidy—and that’s what it is, a mode of social welfare—has been funded with more new growth and with debt, but both have their hard limits, and sooner or later a crash is inevitable, which would significanly affect the entire economy. That is, adding insult to injury, single-family suburban housing developments and big box stores aren’t even pulling their own weight, and threaten to drag us all down with them.

As for EVs, true, their owners don’t have to pay for gas, but they might want to put some money aside on a regular basis to cover the quite costly battery replacement when the day comes. Also, if the heavier weight if EVs will lead to more deaths and injuries, it would be equitable for their owners to pay higher insurance premiums at the very least.

ENVIRONMENTAL DAMAGE

“In the planetary boundaries framework, six of the nine planetary boundaries have been transgressed [and] automobility has contributed to the transgression of at least four of these boundaries: climate change, biosphere integrity, land system change, and novel entities.”

16. Carbon emissions (B)

How much do cars contribute to CO2 emissions? The figures vary from source, but those used by these authors fall in the usual range: transport is 23% of global energy-related CO2 emissions, with 70% of that being from “road vehicles.” However, tailpipe emissions don’t tell the whole story, with other emission sources being production, operation and maintenance, provision of fuel and electricity, disposal and infrastructure. Comparing ICE vehicles and EVs, the authors state:

“Internal combustion engine vehicles produce most of their emissions in the operation stage, with 23–32 t of CO2, and the production stage, with 5–10 t. Electric vehicles produce most of their emissions in the fuel or electricity provision stage, with 11–20 t, and the production stage, with 9–14 t.”

Which is 28-42 t for ICE vehicles and 20-34 for EVs. That’s certainly less for EVs but not as much as I personally thought it would be, the way they’re pitched.

Then there’s the carbon emissions related to building and maintaining roads, parking and other infrastructure like gas or charging stations. The authors also note that “locking in” the sprawling land use style of car-dependent environments makes it more difficult to mitigate for emissions than in denser environments, where energy-saving schemes like district heating and cooling systems can be implemented.

17. Pollution and resource extraction (B & W)

Oil extraction and mining for metals are required for both ICE vehicles and EVs. Though EVs don’t burn fossil fuel for propulsion (B), they have many parts made of plastic, which is produced from fossil fuels, a process emits carbon and other pollutants. EVs also use more mined metals and minerals than ICE vehicles (W). Environmentally, mining is a really nasty activity, affecting local air, water and soil quality, destroying habitat, and more. See my recent article: Copper Mining: Totally Not Green, But Totally Needed for “Green” Energy. The end life of all vehicles results in materials that need to be disposed of, whether in landfills, by incineration, etc., after re-usable and recyclable components are removed.

18. Tires (B/S)

Tires are not biodegradable, and 2-3 billion are manufactured annually. Their ingredients include rubber, carbon black, silicon dioxide, steel wire, nylon and polyester. Much of this is produced from fossil fuels. When they’re word on out, they are burned, buried, or recycled into new products, though such products still contain toxins and must be used carefully so as not to spread these substances further. Pollution from friction between tires and the road is super serious. An estimated 35% of the microplastics in the ocean come from tires and road markings. In the Pacific Northwest, salmon populations are threatened by tire substances washing off roads into their streams.

EVs, being heavier than ICE vehicles of the same size due to their batteries, produce more friction pollution.

19. Other pollution (S)

Other pollutants include road salt, which impacts local soil and water when it runs off the roads. The authors also include in this category oil spills on the ocean, and the effects of noise pollution on wildlife.

20. Land use (S)

The authors focus on roads, which adversely affect wildlife through road deaths, habitat destruction, habitat fragmentation, pollution, and all the “development” that follows roads wherever they go. Not only do they take up space, but their imperviousness to water leads to toxic run-off and flooding. Wildfire regimes are also altered, both by interrupting historical patterns and by providing new sources of ignition. The authors quote the IPCC: “More than any other proximate factor, the dramatic expansion of roads is determining the pace and patterns of habitat disruption and its impacts on biodiversity.”

I would add other land-use alteration that supports cars and which pollutes or destroys habitat including fossil fuel extraction, metal and mineral mining, pipelines, transmission lines, refineries, factories, etc.

The authors conclude:

“Since their invention, cars and the system of automobility have killed an estimated 60–80 million people, injured at least 2 billion, created or exacerbated social inequities, and damaged ecosystems in every global region. Governments, corporations, and individuals continue to encourage automobility (e.g. through road expansion and electric vehicle subsidies) despite its status as the leading cause of death of children, a major contributor to climate change and pollution, and a system that forces the economically poor to pay for the convenience of the wealthy. The current status quo prioritises the movement and storage of cars above the safety, health, dignity, and well-being of people and the environment. It took just a few decades for nearly every city on Earth to be remade from a pedestrian-centric place to an automobile-centric place. Perhaps in a few more decades, interventions such as those listed above will have once again remade cities—this time into safer, healthier, and more just environments.”

My summary

By prioritizing the car, we have built an infrastructure that is both environmentally and socially disastrous. Car-dependency has devoured resources at far greater rate than previous ways of life and has burdened us with a culture of misery.

Not mentioned by the authors of “Car Harm” is how automobility hobbles us in our efforts to make a better future, politically and socially. Community has been atomized, and with its loss, we are out of practice at cooperation, its beating heart. Sooner or later, one way or another, and probably piece by piece, our current systems will lose functionality and be replaced by something else that actually works for people and planet. Given the intransigence of those on top, that something else will need to be pushed from the bottom up, which will require cooperation. The suburbs, with their architecture of isolation, are a poor landscape for fostering such cooperation.

explores this subject from the point of view of labor organizing in his article, How Sprawl & Suburbs Have Upended the Organizing Terrain, which I recommend.The only solution

There is one way, and one way only, to address all the problems with cars and that’s to reduce the number of cars, no matter what they run on. Two great ways to do this are:

1) Provide viable alternatives to driving

That’s mass-transit which is efficient and pleasant and free of charge, and infrastructure for walking and micromobility (bicycles, skateboards, scooters) that’s safe and enjoyable and convenient.

2) Reduce the need for driving

That’s making our built environment more walkable, cycle-able, reachable by public transit, etc. Start by changing zoning laws to allow more diverse uses. For example, imagine that one house on every suburban block was allowed to become a business, like a corner store, cafe, daycare, pharmacy, salon, etc. Or imagine that classic Main Street architecture were made legal again: 2-3 story buildings, built immediately adjacent to one another, with stores on the first floor and residences above. “Wait, what?” you say. “That’s illegal?” Yep. See: Every neighborhood should have a corner store—but can't and The Lively & Liveable Neighbourhoods that are Illegal in Most of North America. (However here’s an example of a strip mall and its big parking lot being turned into a decent urban space.)

People have been talking about and working on these ideas for decades, so there’s a plethora of literature and other media out there, not just about what’s wrong, but about how to fix it. I recommend checking out these YouTube channels to learn more.

If you’re in a city, there’s likely already folks working on this stuff, so you can jump right in to help make change where you yourself live. These are issues where advocating locally can really make a difference, because that’s the level where the decisions are being made.

Great essay. May I add the impact to wildlife, from migrating butterflies to deer to bears.

As I have been saying for some time, the tunnel vision on tailpipe emissions misses all the other consequences that accompany EVs…

https://open.substack.com/pub/stevebull/p/todays-contemplation-collapse-cometh-f93?