AI/data center backlash vs. the “progress” myth

An Industrial Age narrative at long last faces scrutiny

I’ve been heartened to see the growing pushback against AI and data centers in the United States. AI and data centers are inextricably linked because the former can’t operate without the latter. Voices across the political spectrum have been raising concerns about an array of issues including job losses, rising utility rates, drinking water depletion, quality of life in neighboring communities (noise, lights, traffic, views, property values), government subsidies, ubiquitous AI sloppification, and environmental impacts including energy consumption, water contamination, land use, e-waste and carbon emissions.

I am especially encouraged to see the environment getting some of the attention, given how little it garners these days outside obligatory nods to “climate”; a September AP poll found that 41% of US Americans are “extremely or very” concerned about AI’s environmental impacts, with another 30% being “somewhat concerned.” Only 27% were “not very or not at all” concerned. On December 8, a group of over 230 environmental organizations sent a letter to Congress urging a moratorium on new data centers.

As an illustration of just how broad the pushback has become, Republican gubernatorial candidate James Fishback, who is challenging incumbent Ron DeSantis, pledged to block the construction of “*any data center* that jacks up our electric bills or threatens our water supply.” Though the term “our water supply” is very human-centric, it sounds unexpectedly environmental coming from a Republican. DeSantis, for his part, has proposed an “AI Bill of Rights” that would limit the industry, regulate data center build-out, and “Protect Natural Florida,” which, again, comes across green adjacent. Of course these are politicians and who knows how sincere they are, but the fact that they both felt compelled to say something is a measure of which way the wind is blowing.

At the grassroots level, what’s looking more and more like a national movement against AI and data centers has been notching up real victories. According to Data Center Watch, $98 billion in data center projects were “blocked or delayed” in the second quarter of 2025. Since then, Amazon bowed out of a data center project in Pima County, Arizona, after sustained community pressure that included a unanimous vote against the proposal from the Tucson City Council (though, like a zombie, the project won’t seem to die). Many other proposed data centers are facing stiff resistance.

But what’s most intriguing to me is that I have never witnessed anything like this much pushback against a technological development. During my life, many new inventions have been foisted upon the public without consent which transformed society in part or in whole: video games, cable television, CDs, VHS, personal computers, digital photography, the world wide web, cell phones, social media, smart phones, and streaming media. All of these were criticized, but only marginally, and “progress” always marched on.

AI and data centers are decidedly not enjoying the same reflexive and nearly universal acceptance as everything on that list did. For the first time, I feel like the basis of the “progress” myth is being questioned, if only implicitly. Enough people are asking “Do we need this?” and “Do we even want this?” that I daresay this time is different. And that’s exciting.

The “progress” myth

The “progress” myth is one of the most deeply held beliefs in contemporary Western society. It asserts that new technologies always improve quality of life. Sure, maybe a new invention has some down-sides, but overall the benefits outweigh the harms. The history of civilized humanity is viewed as a ladder, with every new invention or method elevating us above our ancestors in both mental sophistication and physical comfort.

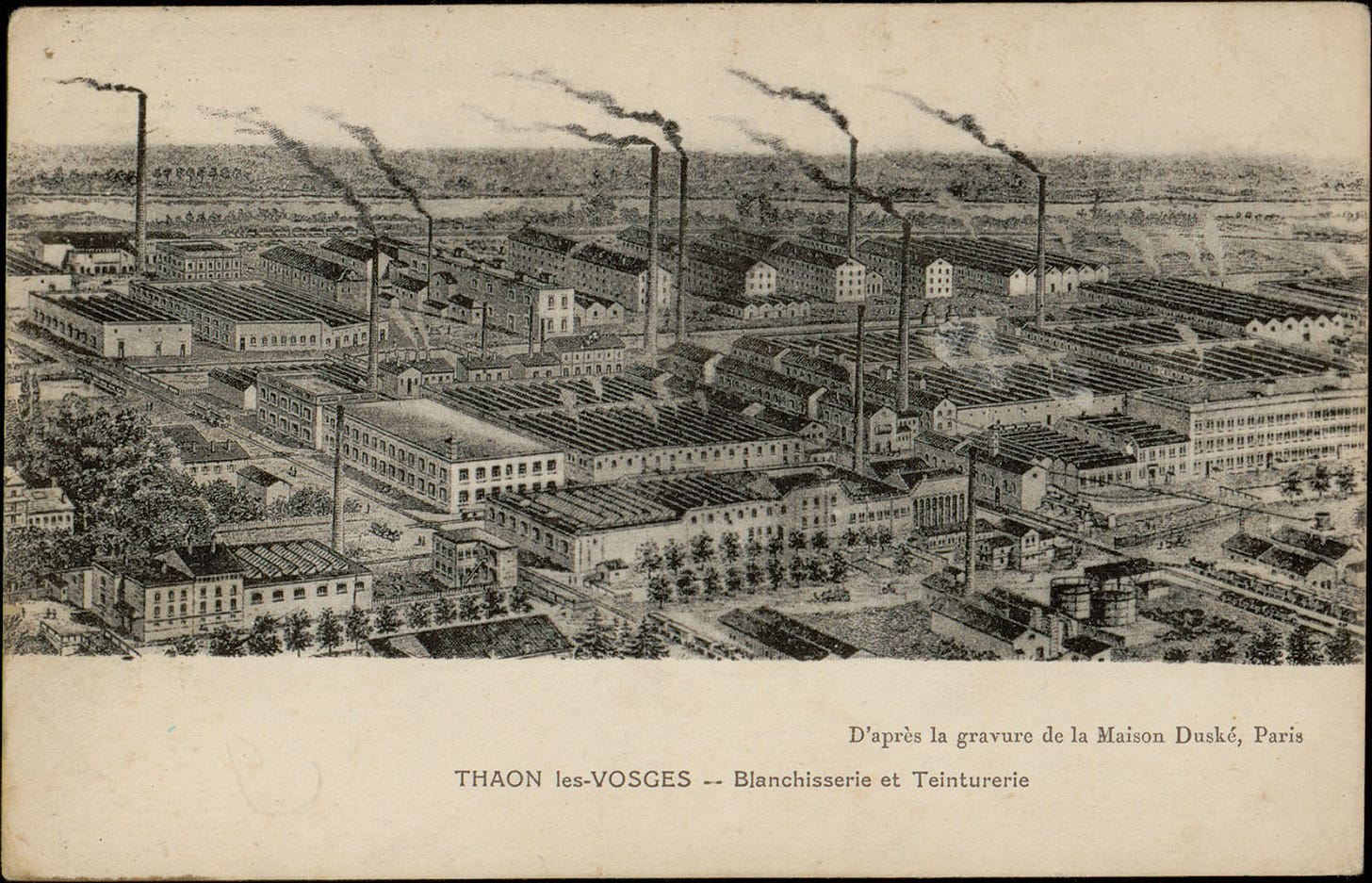

Like many of our cherished, but unexamined—and ultimately false—worldviews, the “progress” myth emerged in Western Europe in the 18h and 19th Centuries with the Industrial Revolution. This was a tumultuous period marked by widespread dislocations of previously stable social orders, during which mechanization supplanted handicrafts and transformed agrarian methods. Everything got turned upside down.

Here I must quote philosopher and historian Lewis Mumford’s brilliant Technics and Civilization (1934) at length:

In the eighteenth century the notion of Progress had been elevated into a cardinal doctrine of the educated classes. Man, according to the philosophers and rationalists, was climbing steadily out of the mire of superstition, ignorance, savagery, into a world that was to become ever more polished, humane and rational... In the nature of progress, the world would go on forever and forever in the same direction, becoming more humane, more comfortable, more peaceful, more smooth to travel in, and above all, much more rich.

This picture of a steady, persistent, straight-line, and almost uniform improvement throughout history had all the parochialism of the eighteenth century: for despite Rousseau’s passionate conviction that the advance in the arts and sciences had depraved morals, the advocates of Progress regarded their own period—which was in fact a low one measured by almost any standard except scientific thought and raw energy—as the natural peak of humanity’s ascent to date. With the rapid improvement of machines, the vague eighteenth century doctrine received new confirmation in the nineteenth century. The laws of progress became self-evident: were not new machines being invented every year? Were they not transformed by successive modifications? Did not chimneys draw better, were not houses warmer, had not railroads been invented? …

Value, in the doctrine of progress, was reduced to a time-calculation: value was in fact movement in time. To be old-fashioned or to be “out of date” was to lack value. Progress was the equivalent in history of mechanical motion through space: it was after beholding a thundering railroad train that Tennyson exclaimed, with exquisite aptness, “Let the great world spin forever down the ringing grooves of change.” The machine was displacing every other source of value partly because the machine was by its nature the most progressive element in the new economy...

Unlike the organic patterns of movement through space and time, the cycle of growth and decay, the balanced motion of the dancer, the statement and return of the musical composition, progress was motion toward infinity, motion without completion or end, motion for motion’s sake. One could not have too much progress; it could not come too rapidly; it could not spread too widely; and it could not destroy the “unprogressive” elements in society too swiftly and ruthlessly: for progress was a good in itself independent of direction or end. In the name of progress, the limited but balanced economy of the Hindu village, with its local potter, its local spinners and weavers, its local smith, was overthrown for the sake of providing a market for the potteries of the Five Townsi and the textiles of Manchester and the superfluous hardware of Birmingham. The result was impoverished villages in India, hideous and destitute towns in England, and a great wastage in tonnage and man-power in plying the oceans between: but at all events a victory for progress. [all emphasis is mine]

In sum:

history is an ascent from barbarism and scarcity to civilization and abundance;

increasingly complex technology is the provider of solely positive outcomes;

the new is axiomatically better than the old;

“progress” is a de facto law of nature, inevitable and irresistible; and

it results in universal advancement regardless of casualties.

If this sounds not only familiar, but fundamental, that’s because this “notion of Progress” remains a “cardinal doctrine of the educated classes” today. As Justin Kollar writes, about a recent report put out by an energy-centered investment firm:

It presents the rise of AI, data centers, and EVs as a naturalized, quasi-inevitable source of load growth. That demand is not framed as the outcome of strategic corporate choices, regulatory decisions, and public subsidies, but as a kind of secular force to which investors must adapt. [my emphasis]

These are corporate people seeking capital so it’s in their interest to present the expansion of AI, etc. as certain, but I’m sure they really believe it too. That’s how unconscious dogma works. This is just one example of the “progress” myth’s persistence that I happened to run across while writing this essay. Others are easy enough to find throughout tech, business and political media once you keep your eyes open for them.

The forbidden question

Mumford again, speaking about the 19th Century:

Life was judged by the extent to which it ministered to progress, progress was not judged by the extent to which it ministered to life. The last possibility would have been fatal to admit: it would have transported the problem from the cosmic plane to a human one. What [industrialist] dared ask himself whether labor-saving, money-grubbing, power-acquiring, space-annihilating, thing-producing devices were in fact producing an equivalent expansion and enrichment of life? That question would have been the ultimate heresy.

When it comes to AI and data centers, that question is now being asked, in myriad ways, by a diverse spectrum of people. Previous innovations offered convenience and entertainment: television brought a visual medium formerly restricted to movie theaters into the home, and choices were expanded by cable, VHS and streaming; personal computers provided a better typewriter, games, and eventually the internet; mobile technology put it all in our pockets. Sure, AI is entertaining to some, but repulses a great number of others. Data centers are this century’s equivalent of sooty factories, degrading quality of life wherever they are sited.

Whose lives are AI and data centers “ministering to”? Billionaires, who are getting less popular by the day for a lot of good reasons. Do they know that the only way to get what they want is to force it on the rest of us? It’s clear they do. Hence the Trump executive order that forbids any state regulation. But rather than ending the pushback, I expect president’s brash action will only fuel it, and kick the fight into higher gear. I’m here for it.

Call out to other creators

We writers and other creators critical of the “progress” myth have been marginal figures for the most part, but with this push-back against AI and data centers, we have an opportunity. People are more open now to questioning the dominant narrative than they ever have been, at least in my living memory. Let’s raise our voices and elevate each other’s work to build momentum together.

If you told me AI has found the cure for cancer and other diseases overnight because it’s so intelligent… or that we are using it to work toward global world peace or reduce suffering, or halt violence, or we will stave off our own destruction because of its intelligence— I might give it another look. But knowing the environmental costs alone— I don’t think we can wait for something artificial to give us a clue as to how humanity survives or evolves. As always, thank you for your words. ❤️

Like the Mongols’ destruction of Nalanda University, and the libraries of Merv, Antiokia, Bukhara, and Baghdad, Silicon Valley’s Tech Mongols are laying similar waste to American education, scholarship, culture, and mental health. In the age of the screen, our humanity is the most important thing that separates us from the unaccountable machine.